Suggestions for Beginners, Reminders for Masters: Some sensible tips and harmless tricks for overtone singing

My first hearing of overtone singing was followed by a period of intense desperation. My despair came with much enthusiasm, but I remember an aching desire to sing the way I heard on the recordings. I reasoned that if merely listening to overtone singing can excite profound fascination in me, than what can actually doing it make me feel? Pure ebullience was my guess.

I sympathize with those who ask “how can I learn to do that?” I know they seek the same feeling I sought. What follows here is a rather incomplete list of suggestions, affirmations, and aphorisms which are in no particular order, but are most certainly not “random” to use the parlance of high-school times. “That was so random,” the young people say, and I do love them all for it. However those “so random” acts to which they refer are usually more deliberate and focused than anything else they have done all day–a foray of full intention, a precise and directed line against the backdrop of a quotidian wash. Randomness should not be confused with spontaneity, but either way–either one–I think we need a lot more of it.

I hope the following list leads you closer to the kind of singing you want to do and the kind of feelings you want to have. Please know, however, that there are no magic words that can give you the skill. You have to play, experiment, observe, and adjust.

1) You can teach yourself. Though learning to overtone sing without a teacher might seem impossible, many adepts have acquired skills while sitting all alone in a room. I learned by listening to recordings of overtone singers from Tuva, Mongolia, Central Asia, North America, and Europe. Within a day or two of obsessive, continuous practice, I could imitate most styles with a reasonable degree of similarity to their sources. I have taught some individuals who catch the “knack”of a style within minutes, and it is very much a “knack” because there is an indescribable trick to turning on the sound, and when you get it, you’ll have it. I believe I got the hang of this with some ease because I’d played the trumpet and other brass instruments for many years before singing overtones. Other brass players have caught on quickly as well, and the “jaw harp”–specifically the tongue placement when playing–shares some very salient parallels with overtone singing.

2) Imitate other singers, but sing like you. All humans, regardless of age or gender, have the same digestive and respiratory components comprising the vocal apparatus. Each voice is unique and truly inimitable. You can waste a lot of time trying to sound like someone else, while your own intrinsic sound is there waiting for you to discover it. Muster the courage to work with your inherent sound because no one else in the world has what you have, and therein lies its value.

3) Listen as much as, if not more than, you sing. Maintaining enthusiasm is necessary to attaining skill and producing meaningful sound–“music” if you dare. But desire can keep you from your goal. In making efforts to produce high, ringing harmonics, the novice strains, pushes, pulls, and all around fails to observe the overtones that are already present in his or her natural singing voice. I recommend first listening for the harmonic overtones in your natural, uninhibited singing voice and, when identified, concentrating intensely upon them. By listening carefully, one learns that there is no need to force the emergence of what is already there.

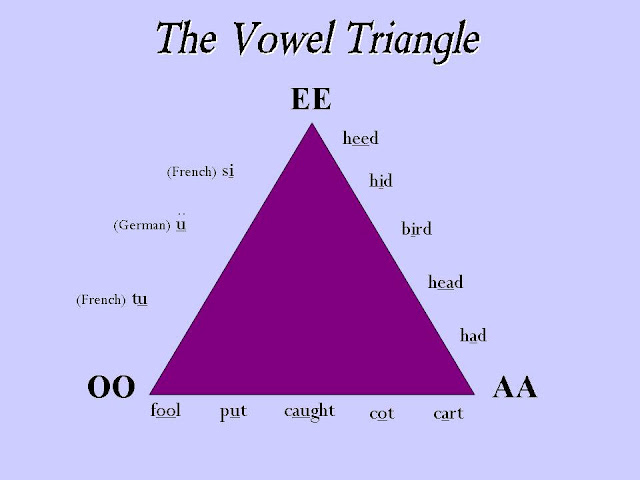

4) Practice intoning vowel sounds while cupping the hand to the ear. Beginning on a pitch in your medium to low register (probably the frequency range at which you speak), intone around the vowel triangle, moving as slowly as you possibly can and breathing comfortably as needed. As you sing, cup your hand to your ear with the palm held slightly away from the jaw line. The cupping of the hand amplifies the higher harmonic overtones that characteristically fall away the moment your sound leaves your mouth and enters into the air in front of your face. I have observed this hand-to-the-ear technique at use in several of the world’s traditional singing traditions. Furthermore, in my opinion, the gesture of putting the hand to the ear helps to redirect awareness from the reactionary mouth to the responsive ear.

5) Practice the three “voices” and making transitions from one to the other. Almost any overtone-singing style is executed using one of three voices. The “voices” are more than just three differing vocal timbres. The first voice, the “neutral”or “natural”voice, uses no more laryngeal tension than is necessary for speech. Second, the “throat” voice (known as the khoomei voice in Tuva and neighboring regions in Central Asia), uses an immeasurable but clearly audible amount of increased tension in the larynx. Technically, the throat voice is made by increasing the length of the “closed phase” in each open-and-close cycle of a periodic frequency. The throat voice is not unique to Central Asia, and it can be heard in parts of Central and North Africa and among blues and rock vocalists such as Howlin’ Wolf and Captain Beefheart. Third, there is the “subtone” voice, which I think of as a kind of extension of the throat voice, but with prominent, and downright unmissable, sympathetic vibration of the false vocal folds and, in many singers, other surrounding tissues of the vocal tract. (For a more complete description of these voices and instructions for how to produce these voices, see my previous post).

When you have learned to do the voices, work on moving smoothly from one voice to the next. Begin with your natural singing voice, on a comfortable, mid-to-low pitch, and increase tension until you move into the “throat voice, and then return to your natural voice. Also, move from the natural voice, to the throat voice, to the “subtone” voice, and then return again, breathing as needed. Remember the exercise is to attempt to make smooth transitions, but the result may be more of a turning on and off of these vocal sounds.

6) To produce the lip trembling effect, purse the lips to the point of muscular exhaustion until they ripple subconsciously. I receive many questions about the style which I have listed on the video as “khoomei borbangnadyyr“, and I have learned from a few viewers that this may be actually named “byrlang.” Like many great things in life, the tremelo effect of the lips is not done consciously. I cannot speak for others, but when I do it, I purse my lips, pushing them forward, and then open them gradually and slightly to find the ideal size of the aperture. Sustaining this position, I feel the muscles surrounding the embouchre begin to fatigue. With only a little time, the lips begin to shake uncontrollably. I love this technique because it illustrates a great truth that there is strength and purpose in weakness. The more you practice the lip tremelo, however, the stronger you make the muscles, and so the more difficult it becomes to fatigue them. But no matter how beefy your chops get, there is always a “sweet spot” somewhere in the positions of the pucker and aperture that is weak enough to surrender to your “hidden will.”

7) Sing outside. Explaining this one isn’t easy, nor is it really necessary. The natural environment is composed of powerful archetypal symbols that positively affect the human organism. The forms of nature–shapes, sounds, smells, textures, tastes–instill quietude and awareness that is conducive to overtone singing. I have a theory as to why, but I don’t want to write about it write now. You may find that the most pristine outdoor locations–edenic sanctuaries in your own backyard–inspire you to sing in this way. Moreover, many overtone-singing traditions have strong ties to the natural landscape and its myriad creatures.

8) When you sing a sound you like, don’t celebrate too soon; instead, take a moment to reflect on and remember the sensation of how it felt. Finally getting it can leave you so excited that you neglect to notice how it feels when you perform correctly (by correctly, I mean the way you want it to sound). Rather than going to show a friend, setting up the recording equipment, or running to your dad’s house to sonically heal his eczema, relax and observe your physical sensations and mental attitude that led to the successful performance.

9) Move through the overtone series as slowly as possible. Beginners often try to move up and down the overtone series too quickly, racing about and making articulatory movements too gross for stability. When you find three, two, or even one overtone(s) you can sustain with some clarity, stay there….enjoy that sound. Moving slowly is not only more difficult than moving quickly, but so too one can develop more control and usually derive more musical pleasure and meaning from singing within a limited range of the series; at least, at first.

Aside from these nine simple suggestions, I can offer no more tips to mastery of overtone singing in all styles. It is impossible for, if not detrimental to, a student to receive a handful of universal, fix-all tips. A teacher must hear and see a student to make a proper assessment of a student’s ability and potential. There are too many variations on physiology and methods to help anyone without virtual or actual contact.

Finally, to reiterate, skills can be discovered and perfected all alone in a room. You don’t need a cave, or a mountain top, an emaciated guru, or a trip to “exotic” locations to learn to overtone sing. Though I believe one can come to know the world from one spot on the floor in the house one was born in, there might be some truth to authenticating some styles by visiting specific locations on the planet. I just don’t know for certain. But do beware of authenticity, as most of the time, whenever authenticity arises in a discussion, there is a either a personal or cultural ego fighting for superiority over another. Oh, and money–authenticity debates and money seem to go together like rich kids and belted, khaki shorts.

“Ours is better than yours”—what an asinine statement. If such debates arise around you, get away from those people and go to nature, an entity which has no need to justify its identify, and so it lives on and on.

Singing Undertones, Subharmonics, and Subtones

How does one learn to sing those seemingly super-low tones? Some people are as obsessed with low notes as they are with the high ones. For whatever reasons, the extremes of anything are attractive.

Vocal infrasonics can be heard in various traditions: the yang chanting used ritually among some branches of Tibetan Buddhism; the folk music and throat-singing of Tuva (kargyraa) and Mongolia (kharkhiraa); the liturgical music of Sardinia (in the tenore bass voice): alongside the umngqokolo overtone singing of Xhosa women; and either occasionally or continuously in the epic songs of the Altai, Khakassia, and Sakha Republics.

But the ability to produce subtones is inherent in the human vocal apparatus; consequently, this vocal technology also arises spontaneously and radically, which is to say, devoid of roots in any of the above-listed traditions.

I used to tell people that to sing subtones they simply had to hit “second puberty”. Though the joke has since grown tiresome, there is truth to the onset of a lesser known secondary pubescence. At about the age of 26 years, the human brain typically ascends to another plateau of cortical development, whereby the pre-frontal cortex fully matures. Think back (or forward) to your twenty-sixth year or when-a-bouts. What was happening at that time? How did you feel? Anything change?

Perhaps at twenty-six your voice didn’t start to sound like a chainsaw at the bottom of a well, but still, maybe we should rethink the concept of only one puberty, only one turning point in the ongoing development of the remarkably intelligent organism that is human body.

Overtones and Undertones

Overtones exist. There is a clearly observable and measurable series of harmonic overtones that is inherent in periodic sound vibration. Overtones go over the main note, but is there a series of tones that go under the main note?

Is there an undertone series?

In formal acoustics, the undertone series remains a theoretical construct, not an actual acoustical phenomenon. To date, no one has produced evidence of an undertone series, a true mirror inversion of the overtone series that sounds simultaneously with the fundamental frequency (With singing, the fundamental is the actual note sung by the vocal folds).

|

| Theoretical Undertone Series to the Fifth Partial |

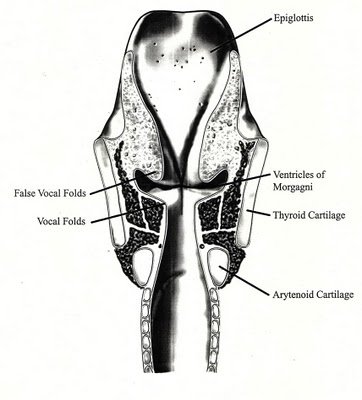

What is that low tone if it is not an undertone? I prefer to call it a vocal subtone, as it is caused by the oscillation of tissues that lie above the vocal folds. We use the vocal folds for everyday speech and song. The tissues above these actual focal folds are known as the false vocal folds, and you can see them on the diagram below, which is a cross sectional view of the larynx.

When the actual vocal folds are set into periodic vibration with a highly tensed glottis, the false vocal folds are pushed together and slightly upward toward the back of the throat. I have imagined that when these slimy little flesh curtains are set into motion to produce a subtone, they look and feel like puckering lips.

When set into motion, these false vocal folds vibrate most optimally, with maximum amplitude and consistency, at exactly one half the rate of vibration of the actual vocal folds. For example, if your actual vocal folds are singing an A 440 Hz and you set your false vocal folds into optimal vibration, you will produce a strong subtone of 220 Hz simultaneously with the 440 Hz tone of your actual vocal folds. Thus, you are producing two distinct oscillations spaced one perfect octave apart.

For this reason, I prefer to use the term subtone instead of subharmonic or undertone to describe this phenomenon, as the secondary tone is not a partial harmonic of the actual note sung, but a distinct fundamental tone unto itself. Furthermore, being a tone unto itself and not just a partial, a subtone also has a corresponding overtone spectrum.

Remember that overtones are parts dependent on the whole, which is the fundamental vibration. Overtones do not have overtones, nor should undertones have overtones.

Does this remove the mystery from subtone singing? Not at all. We’re merely taking out the mystery and then putting it right back in again.

No one knows exactly why the subtone vibrates so supremely at exactly one octave below the fundamental. Resonance might begin to explain it. The false vocal folds might absorb more energy when the actual vocal folds matches the resonant frequency of the false folds. However, one can sing a whole scale in subtones, which indicates the false vocal folds have an atypically wide range of resonant frequencies. Furthermore, the vibration of the subtone far exceeds the intensity of the vibration of the actual tone, and the false folds feel and sound as though they are not merely absorbing energy, but producing it independently.

There you haven’t it: the mystery remains.

How to Sing Subtones

1. Sing any tone naturally and slowly slide it up a little ways, and then go all the way down to the lowest note your can sing comfortably. Hold it.

2. From that low note as your base, sing up about a perfect fifth (the opening interval of the Star Wars theme, the Superman theme, the E.T. theme, or the opening notes of just about anything by John Williams).

3. Starting on that note about a fifth up from your lowest, begin to hum. For a few minutes, just practice holding that hum steady to get comfortable with your note.

What follows is the hard part, and no “how to” explanation will be universally applicable to each individual, but try this anyway:

4. Pretend you are pushing an immovable object with all your strength and then grunt. Sustain the grunt as you sing your note. You should be feeling a lot of pressure building up beneath your throat, in your lungs, and all the way down to your lower belly.

5. With that feeling of pressurization in your torso, imagine you are pushing up from the back of your throat where you feel normal vocalization while pushing down from somewhere a ways behind the base of your tongue. This is a difficult sensation to feel and remember, and most people feel more upward push from the back of the throat than they do downward push from the base of the tongue. There should be a sensation of the back and front meeting somewhere in the middle, where we find the false vocal folds.

6. While pressurized and pushing the throat, begin to do the grunty hum and then add just a touch of cough and hack while continuing to sustain your note.

7. Slowly and carefully adjust all the physiological parameters (degree of tension, placement of tension, pitch of your note, vowel, mouth open, mouth closed, seated or standing, morning voice or night voice, etc.) until the subtone appears. When it does appear, don’t chase it. Take a moment to stop and become aware of how it felt and sounded. Much of the learning here is in deeply internalizing a physiological memory of the sensation.

When you achieve a consistent subtone, you will know it. The sound will be strong and it will seem to just lock into place on its own.

Three Common Mistakes

1. Going too deep. When singing a subtone, you are not singing a low register note with the actual folds. The actual folds are actually singing a relatively mid-range note, and the false vocal folds are resonating at one half the rate of the actual folds. Similarly, beginning subtoners often associate the deepness of the subtone with deepness in their body. As a result they tend to put the sound too deeply in the throat to produce a gravelly rattling that feels like it is going into the chest—it’s kind of an old-man-with-his-orange-juice-in-the-morning sound. But the vibration of the subtone is actually above the vibration of normal vocalization. Send your awareness of the sensation upward, not downward. However, also keep awareness in the root of your body, at the base of your belly and even lower, from which the energy of this sound must come. I know it is confusing when you think about it, as there are lots of paradoxes in this kind of singing. Doing will make it clear.

2. Vocal frying. One can produce uber low vocal tones by loosening the glottis to regulate the incoming puffs of air. These bubbly pops can be regulated to produce a false bass register, sometimes known as strohbass. In the morning, you can really get those low pops on or around the vowel “uh”, and you can make them go faster and faster until they resound a steady low tone. The vocal fry sounds primarily from the slack closure of the actual vocal folds. The sensation is completely different from subtone singing, which is an intense and simultaneous vibration of the tissues above the actual vocal folds.

3. Over-Practicing. When I first started learning subtone singing, I did it for about 3 hours the first day, 6 hours the second, 8 hours the third, and none for the the 5 days that followed because my voice disappeared into infrasound. For a while I was speaking so low I could only speak in rhythm. The moral of the story is, you must proceed very carefully and patiently. Your false folds have lain dormant for most of your life, and now you’re asking them to wake up and vibrate. With gentle and moderate daily practice (no more than 7-10 minutes a day when first learning), the false vocal folds can begin vibrating freely and with no tickling or discomfort. The beginning subtoner, however, must endure some mild tickling and slight irritation when setting into motion the tissues of the false vocal folds. But with a little time, even the most intense sounding subtone vibrations will not and should not hurt if done properly. In this context, and perhaps many others, doing properly means simultaneously relaxing some areas of your body while tensing others.

Still Mystery

Finally, though at first you may have no idea how to do this kind of singing, you will have no doubt whatsoever when you have done it. The subtone will resound with such purity that you will just know that something mysterious still lies at the back of your throat.

What is Overtone Singing?

Because of the high number of nearly identical questions I have received about overtone singing, I have had to post a blog to save my finger tips, which as a result of my impeccable reply rate, now feel and actually look a bit like the surface of a stale Triscuit Cracker. I may never use a Blackberry again. But no loss. Moreover, people want to know more about overtone singing, and I’ve heard they are having a hard time finding answers.

I promise this will be the most boring of my blog posts to come, for I must get the basics out of the way before I get to the good stuff, the juicy stuff, the stuff that you don’t even have to chew to swallow. But you must first learn what follows.

|

| Overtone Singing with a tampura |

A vocalist who sustains a steady tone while simultaneously isolating and amplifying distinct frequencies above it, uses a technique commonly known to the west as overtone singing. When manipulated to appear distinct, harmonic overtones of a sustained tone are usually perceived as ethereal, whistle-like pitches occurring above or within the sustained tone, and the overall, gestalt effect of overtone singing is of a singer producing more than one note at a time, usually a drone and melody that, for some, brings to mind the bagpipes.

Still don’t get it? Don’t expect to completely understand how overtone singing actually works. I have been singing and studying overtones for ten years and still feel baffled when contemplating this vocal art. Overtone Singing leaves people fascinated in the aftermath of their initial shock of first hearing. And the mystery does not end; in fact, as one learns more, the mystery grows exponentially more profound. So be patient with yourself, and appreciate that the world still holds a little mystery.

I shall attempt to provide the simplest explanation of those whistling tones you hear above a guttural drone, those ethereal little melodies weaving atop a steady pitch. Here it is:

We live our lives inside an unending melody, and most of the time, we are oblivious to this music that is the ever-present harmonic series.

I might just be able to prove this to you right now. Get comfortable in your seat, relax from head to toe, bring your awareness to the sounds around you, and do not judge the sounds as they enter in to the forever-open holes at the sides of your head. Now, you might be listening deeply; at least, deeper than before. Next, breathe in all the way to the floor of your belly, and sing–don’t just say–a steady “Ah” for the length of about one full breath. You might believe you have just sung a “note”, but in the real world–in the world of unending melody–you have actually sung several distinct notes.

Congratulations on taking the first step out of audial oblivion.

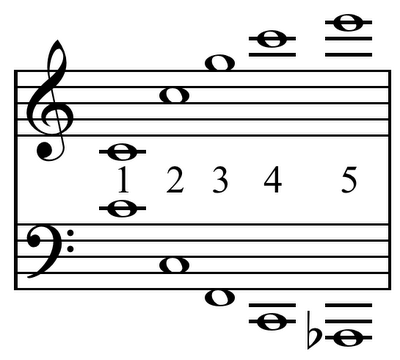

|

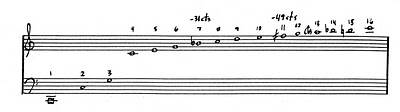

| Harmonic Series to the 16th Partial |

Sound is the result of air molecules energized into motion by vibrating matter. When something vibrates it absolutely must produce a series of tones above it; however, there are exceptions. But most of the time, these little tones are locked in to a pattern of fixed positions that are immovable. This lawfully organized pattern of tones appear in musical notation above, and it is called the Overtone Series, or the Harmonic Series.

If you don’t read musical notation, you can still observe details in the patterns. For example, the tones go up the page and, the farther they ascend, the gaps between them become smaller and smaller. Other patterns can be observed.

Do know, however, that the overtones do not end at number 16 as I have listed here. Actually, the harmonics continue to ascend way higher, and theoretically above the highest limits of the range of human hearing (max. 20, 000 Hz). I have listed the harmonics within this limited scope because the most overtone singing is performed within this range of the harmonic series.

With all that said, I have yet to explain how it is done.

The scientific explanation won’t help you learn to sing overtones, but put simply, overtone singing involves tweaking areas of resonance in the vocal tract and oral cavity.

You tease your mouth and throat just enough until the overtones come out the way you want them to. It’s kind of like the hardware foreplay involved when putting a key into a reluctant lock. You know, whenever you have to cat sit for a friend, you always struggle a bit with the front door, but each time you put the key in the lock, you get a little bit better at getting in: For all things, we must endure a period of awkward acclimation. But you’ll get nowhere fast if you don’t listen hard. Well, not so hard you block yourself, but you must learn to augment your hearing sense.

I learned to do overtone singing and Tuvan throat singing (see video demonstration below) by listening very carefully to the sound of my own voice. Sounds a bit narcissistic to sit in a little room for hours on end and listen to myself, but I wasn’t talking or saying words, and somehow that makes it more normal. Instead, I was sustaining steady long tones on different vowel sounds.

Then, something switched inside my awareness. To describe the sensation is difficult, but the closest comparison I can think of is to the perception of color. Imagine going through life without ever having seen the color green, or perhaps you somehow filtered out just a certain shade of the color green. One day, you see it, and this new addition to your repertoire of perceptions, energizes and inspires you. You might say, “The world isn’t so boring after all! There is still hope for unending fascination!”

Those were my words exactly when I first heard the tones inside my voice. I heard not just a bland drone that carries quotidian speech laden with signification, but a full chord of rich musical tones sounding out what seemed to be the music of the whole universe, and right there inside my little voice. I could hear nebulae exploding, black holes sucking dark matter, whole galaxies colliding, and an angry neighbor pounding on the wall with the handle end of a Swiffer.

Hearing the harmonic overtones in my voice opened my ears and, consequently, opened my awareness.

With my third ear open and my third eye in tears (what could have been taken merely as the sweat of my brow), I practiced listening and singing, seeking out recorded examples of overtone singing and imitating them, until I could somehow intuitively just do any overtone singing style I heard. I now believe, however, that I had a tool that worked in my favor.

When I first began to sing overtones in winter 1999, I was also practicing self-hypnosis, and oh, what a tool it is. No, I didn’t dangle a pocket watch in front of my own eyes until I monotoned the words, “I hear and obey.” Instead, I practiced a method of inducing a state of relaxed awareness that summoned a deeper intelligence from within me. While in this state of relaxation, something akin to a meditative state, my subconscious mind rose to the fore, where it could more easily perceive and execute the singing of overtones.

To sum up how I learned this, I merely listened carefully to myself and to recorded examples of overtone singing and relied on my subconscious mind to do the learning.

However, I have since found ways of helping others find the harmonic series and sing with it. I have observed many students attain overtone singing skills within an hour or two. Learning to be musical with overtone singing techniques, however, might take a little longer, for just how long does it take to become musical? Seems to me that it is always there, lying dormant, until we are ready to risk heightened sensitivity.

Meanwhile, as one begins to hear overtones in one’s own voice, the sonic world begins to change. One starts to hear music in what was previously thought to be the most unmusical of places. I remember hearing a jumpy vacillation between the 6th and 7th partials of the harmonic series in the spiraling water of a toilet bowl. I remember trancing out to the beautiful and endless shimmering ring of the 11th partial above the droning hydro transformer in the grocery store parking lot. I remember hearing folky pentatonic melodies– jigs, almost–when my housemate underwent his nightly oral hygiene ritual using his Philips Sonicare electric toothbrush.

I also remember hearing the music of sound in more organic and less gross settings. I heard it in the winter wind singing through the tops of tall Balsam Firs; I heard it in the humble trickle of a dying stream at the center of a forest of cedars; and even in the breathing of a newborn human infant and the joyful weeping of its host.

Thus, the unending song of the harmonics is all around us, and if we give ourselves over to listening, the harmonics sing themselves.

Before one can sing overtones, one must first practice hearing them.